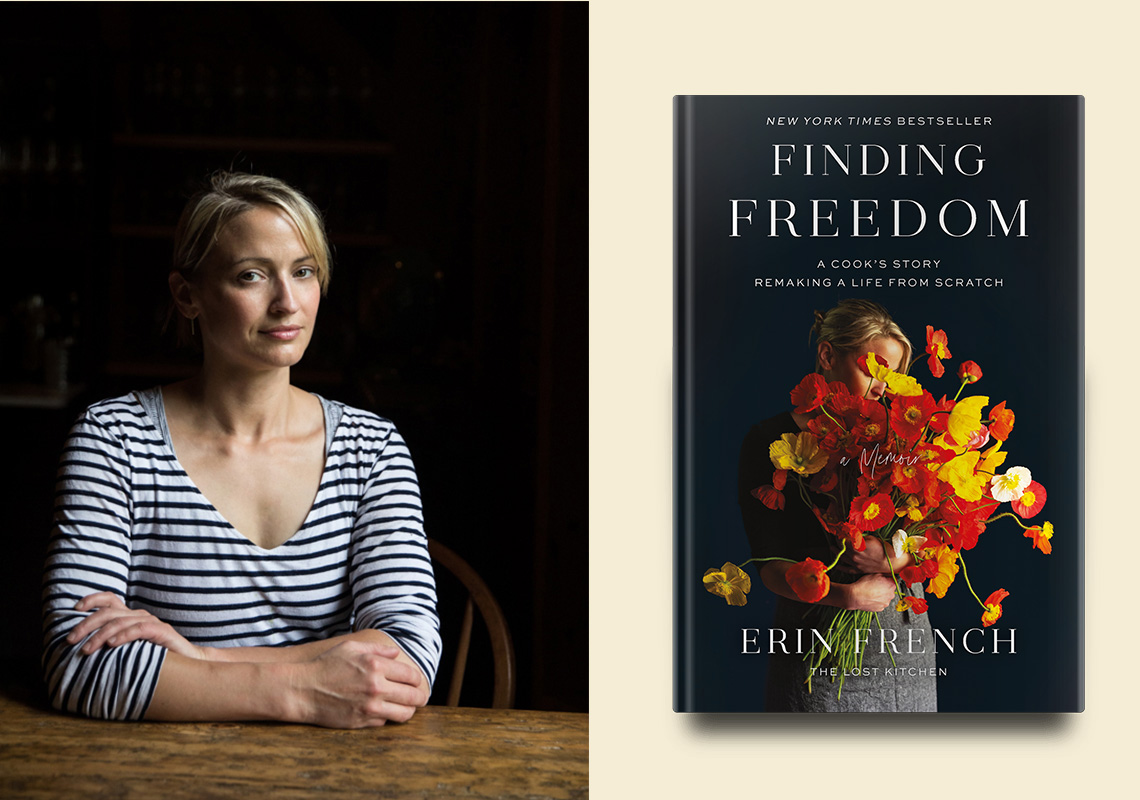

Success did not come easily to Erin French, the renowned chef and owner of The Lost Kitchen in Freedom, Maine. Celadon Books sat down with the author of the new memoir Finding Freedom to talk about how her struggles led her to where she is today: home.

Celadon: Before your wild success with The Lost Kitchen, you faced extreme hardships: single motherhood at a young age, substance abuse and addiction, a toxic marriage and bitter divorce. What lessons do you take with you from those tough times?

Erin French: I’ve been thinking a lot about lessons right now. Just when I’d finally thought, “Okay, you did it. You bounced through so many tough times and now you’re clear sailing,” along comes a global pandemic to completely derail us all. So, here we are in another tough time. And I think COVID continues to teach me about myself, my ability to adapt and overcome, my stamina and strength … or at least what’s left of it. Whatever the case, we have to keep moving forward.

If there’s anything that I’ve learned, it’s that all the hard times I’ve been through — the potholes, the challenges, the missteps — have actually shaped me, defined me, and forced me to look at myself closely to see if I had the ability to rise. I believe that you’ll always find your greatest strength in your weakest moments if you allow yourself to dig deeper than you thought you could ever dig. So yeah, I did find strength in those moments because I was in survival mode.

I look at my life now, and I think of the things that got me here and realize that I needed all of that shit to happen or I wouldn’t be here. So now I can’t help but celebrate those tough moments in my life.

Celadon: Through your darkest moments, the one constant support in your life was your mother. Tell us about your relationship with her.

French: My relationship with my mother has really been a relationship of evolution. When you’re a kid you look up to your parents for answers and for guidance, but my mother was never really guiding me. She never fed me the answers or told me what to do. She just wasn’t that kind of person. I think of her relationship with my dad, and she wasn’t one to speak up. So, I wouldn’t describe my mother as an emotionally strong woman, but she had this immense physical strength. She taught me to be creative and industrious. She taught me the importance of perseverance if you wanted to get something done or make something happen. Whenever she wanted to conquer a project, she’d just conquer it … and it was always great. But on the other hand, she wouldn’t necessarily stand up to you if she didn’t like what you were doing or saying.

Now I think my mother looks up to me for bits of strength where she lacks it, and I look to her for the bits of strength where I lack it. We look to each other for the things that the other might be better at. We look to each other for friendship and confidence. And in my adult life, we’ve inspired each other by coming together and complementing one another’s individual strengths, abilities and points of view. We’re stronger together.

Celadon: Your experiences with your sister and father are more complicated. How do you stay connected to loved ones who have hurt you in the past?

French: For me, that’s been a lifelong continuation of figuring out how to find the right compromise, patience, and acceptance to be in a healthy relationship. I love my father and my sister. But it’s a challenging love and a love that I still struggle with. I realize I can’t change their behavior, I can only change mine. Sometimes it just involves saying “Okay, I know who you are, and I’m just going to have to stay a little bit in the distance over here.” It’s definitely something I continue to struggle with — how to love these people. Our relationships are challenging at this moment, and I don’t think they ever will be easy. I think all I can do is try to be flexible and open to them, but hold my ground on boundaries I need with them.

Celadon: They say it takes a village, and you have found your tribe of women in Freedom. How have they helped shape your definition of womanhood?

French: I think we have all shown each other how strong we are not just as women but as people. But I don’t think I’ve ever fully understood the power and the strength of being a woman until I came together with this group at The Lost Kitchen. It was something magical and powerful that happened organically and without force as if almost by accident.

There’s pride and strength and continual growth and celebration. There’s this feeling of being really comfortable and confident, especially as rural women in the middle of nowhere. We are proud of the work we are doing and the community we are supporting and our abilities to balance it all with family and home life. So it makes me realize just how proud I am to be a woman — and I’m proud of the women around me — but my womanhood does not necessarily define me.

Celadon: It’s clear that you’re a natural artist, from the beautiful food and spaces that you create. What helped you cultivate your artistic eye?

French: For me it was my environment, nature, my mother’s gardens. A few people in my life inspired me, like a friend of my mother’s who always wore the coolest barn coat. There are certain ingredients that give you a feeling when you look at them. When I would look at nasturtium as a kid, I could feel this little ray of sunshine in me. Those are the moments when you have to say, “Okay this is meaningful in some way.” How do you take this thing and express it? Sometimes I don’t know. Maybe it’s just listening to the bright shining moments that bring you joy and bringing them into the forefront in your world.

Celadon: You describe dishes and ingredients in such vivid and loving detail. What is your favorite food memory?

French: One of my favorite food memories? Boiled corned beef and cabbage dinners on my birthday. My grandparents would come over and there’d be this big steaming pot of slow-cooked meat and vegetables. Those were big, celebratory days. Another one would be being barefoot in the garden and eating a fresh cucumber still warm from the sunshine, still prickly because it still had spurs on it that hadn’t been washed off yet. You didn’t even need to wash it. Just bite it, and it was crispy and delicious and there was no other flavor like it in the world. Or then there was playing restaurant with my sister at home, watching my mother’s joy as we served her hot dogs, or whatever, for dinner. It was all so simple and fun and she loved it.

Celadon: How has living amongst nature and farmland helped shape your values in relation to food?

French: Being around nature as a kid was all I knew. I grew up knowing that there’s nothing better than freshly-grown and picked food, and I definitely took advantage of those things when I was a kid. I didn’t know that there was anything other than a cucumber fresh from the garden or warm eggs from the chickens in the coop. We just thought, “This is the way the rest of the world is.” It’s not, but this is the way I started looking at food at a really young age. Those things were singing to me. And now, whether I’m cooking for customers at my restaurant or dinner at home, I always say that the best meals come from the heart and the best ingredients come straight from the farm. We are lucky to be living amongst nature and farmland.

Celadon: In Finding Freedom, you searched for happiness outside of your tiny hometown, but, in the end, it was exactly where you were meant to be. Tell us, what does home mean to you?

French: I’ve been thinking a lot about that. Home, for me, is the place where you feel safe and the place where you feel loved. It’s a feeling. I’m finally home, here in my old house. I’m miraculously here.