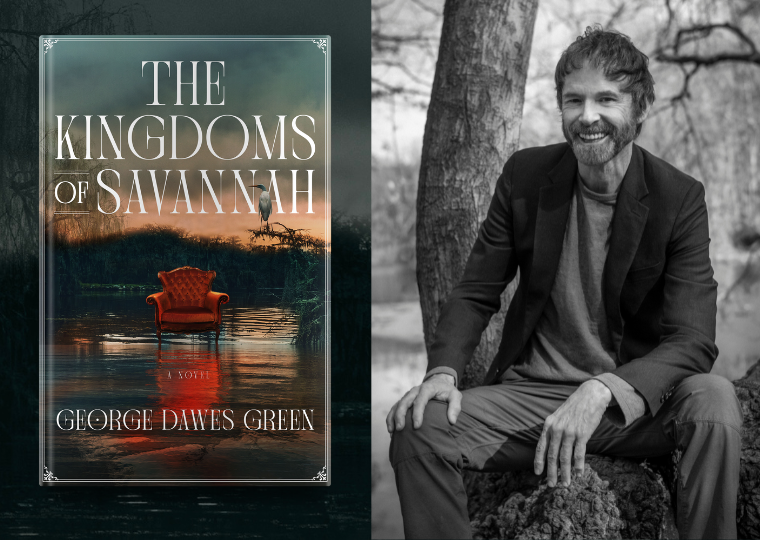

Savannah may appear to be “some town out of a fable,” with its vine flowers, turreted mansions, and ghost tours that romanticize the city’s history. But look deeper and you’ll uncover secrets, past and present, that tell a more sinister tale. It’s the story at the heart of George Dawes Green’s chilling new novel, The Kingdoms of Savannah.

As an eighth-generation Savannahian, did you always know you would write a book set in your hometown?

Actually, I grew up on an island just down the coast from Savannah. But my mother always called Savannah ‘‘our capital city,” and she traced our ancestry back meticulously though those eight generations. When I was a boy, Mom and I often drove up to town, in our bargelike Chevrolet Bel Air. Mom drove slowly, and wore beautiful hats. The city was in ruins in those days. Ethereal and haunted and crumbling and dripping in Spanish moss. We went to visit our second cousins, several of whom were named Inez, which was also my mother’s name—our cousins called her Little Inez to distinguish her from her grandmother Big Inez, the great turn-of-the-century plantation-house matriarch. We sat in stuffy parlors and drank iced tea, and the Inezes told me stories about the long-dead Big Inez and how much better things were in those days. Sometimes my mom organized parlor séances. We arranged ourselves around a three-legged table and put our pinkies together, and the Inezes and I communed with Big Inez. Mom would call out the letters of the alphabet until Big Inez would suddenly cause the table to rap the floor smartly. And so messages would be spelled out, in a slow spirit-code. Mostly Big Inez was giving us her critique of modern life. But sometimes she gave us memories of her childhood, of Sherman’s March and how awful that had been, and how our ancestors had so bravely endured the dispossession of our land, blah blah blah—all the stuff I called “Confederate vamping.”

To me, these sessions felt like arabesques of lies designed to distract me from the true horror of my heritage. When I was 15, I got out of there: I stuck my thumb out and hitchhiked to New York City. I fled.

Still, the city had leeched into my blood. And years later I came back down to Savannah and bought a Victorian house here…and began to think that one day I’d like to try to stitch these Inezes and those stories into a novel.

Please talk about the two versions of Savannah that you present to the reader—the one that the tourists see, and the hidden one that unfolds over the course of the novel.

Tourists imagine they get the character of the city in these tours, with all the mansions and fine silverware, and all the floating Victorian specters moaning about their Lost Cause and their fallen nobility; with all those murderous children and rich heiresses throwing themselves tragically from cast-iron balconies. But Savannahians can’t stand all that death-cult stuff. The real city comes to us through its living stories: the immeasurably rich memories of our neighbors.

What is the significance behind Kingdoms being plural in the title of the book?

There are many worlds in this small city: the redoubts of the old guard, the Black neighborhoods, the 39 homeless camps that encircle the city, the tourist district. As my protagonist Morgana Musgrove says: “Savannah’s not just one realm, it’s a great many realms—but they work together to keep us in thrall.”

Your book features a unique cast of characters, from Savannah’s high-society elite to the working class and the homeless. Which characters felt the most familiar to you?

To create Morgana, I started with my great-grandmother Big Inez, then mixed in a measure of my mother and an equal measure of author Rex Stout’s infamous armchair detective Nero Wolfe. For Willou, I used a sister and a cousin; for Ransom and the community of the unhoused, I had my own memories. All the characters in this novel are built of myself and my family and dearest friends, so they all feel close to me.

This is your fourth novel. In what ways is The Kingdoms of Savannah similar or different from The Caveman’s Valentine, The Juror, or Ravens? Do you feel your writing style or approach to writing has changed since your last book?

I do love the immersion of thrillers—the sense of being swept along on a wave-crest of suspense from page to page. I hope I capture that feeling in Kingdoms, but I’m also trying to sketch the character of a city built on stories, so I’d say this one isn’t a straightforward thriller—it’s got something else brewing.

But then, I guess that was true of my earlier thrillers as well.

In addition to being an author, you’re also the founder of the literary storytelling platform The Moth. How has being an oral storyteller impacted your process as a writer?

The Moth helped me to see stories as the core of human experience: Our cultures are woven around the stories we tell. But I think I’m not so much of a storyteller as a listener. At the Moth, I’ve heard literally hundreds of stories, from all over the world, many that have touched me profoundly and maybe altered my own voice. Yet to me the best tales, the ones with the deepest rhythms and the most moving turns, come from my old Savannah—stories told by Edgar Oliver and Brenda Mehlhorn and Cornelia Bailey and Jane Fishman and Vaughnette Walker-Goode. And my mother, of course. And all those Inezes. I know I’m biased. But on our website thekingdomsofsavannah.com, you’ll find videos of these Savannah raconteurs: Go listen to judge for yourself.