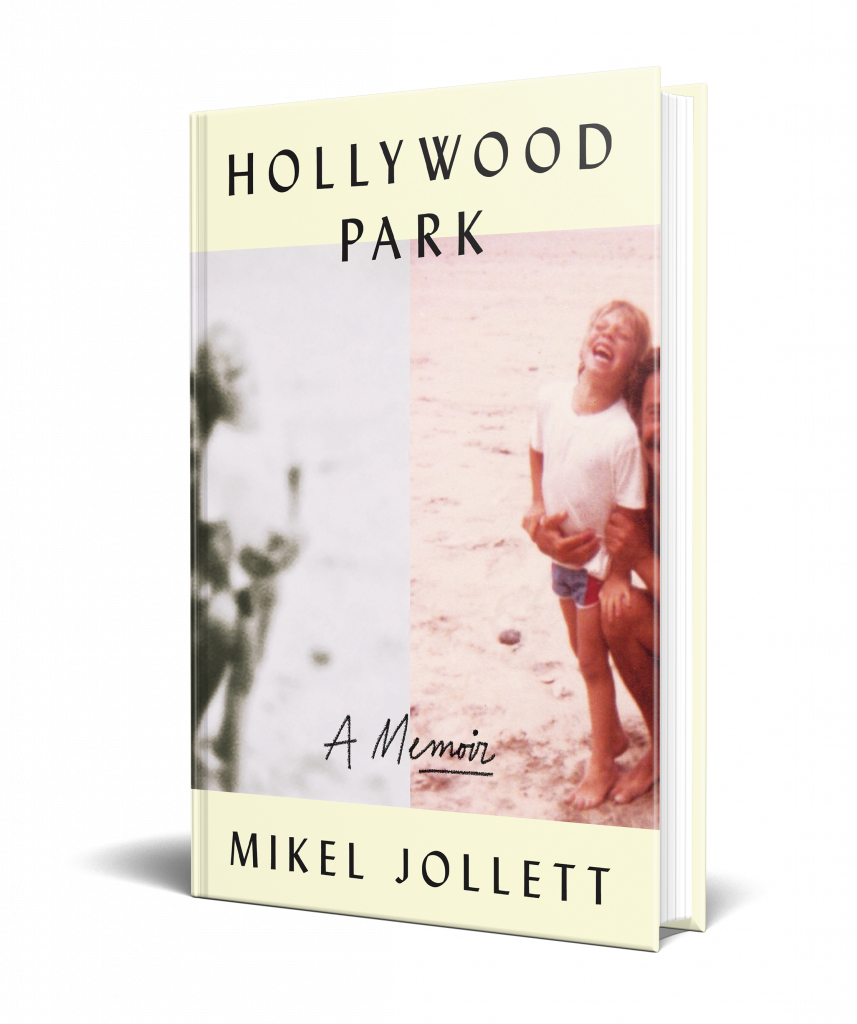

Hollywood Park is the memoir of musician Mikel Jollett, who was born into the California cult Synanon. Jollett sat down with Celadon to tell us about his earliest memories, his complicated relationship with his mother, and how it felt to remember his beloved father through his writing.

By Jennifer Jackson

In the first chapter of Hollywood Park, your mother wakes both you and your brother Tony in the middle of the night to escape from the cult Synanon in Northern California. How clear are your memories from the time you lived there?

I remember a big golden field with trees at the edge behind the building where we slept. I remember my parents coming to visit (separately) and wondering why they had to leave. I remember people yelling. I remember the plaid blankets, story time, and Bonnie, my caretaker, who I loved.

I mostly grew up in the wreckage of Synanon, since we left when I was so young. It came to me like a puzzle I had to put together, almost like separate realities with different rules: Here are the Rules According to Synanon (you have no parents, you are a new type of human who doesn’t need them, nothing is yours), here are the Rules in the Great Big World (no one talks to each other, you’re very poor, your mother is very sad). It took my brother and I a long long time to piece together the reality that a functional adult might have about the situation, that we’d escaped a cult that had once done good things for addicts (including our father), that our mother was severely depressed, and that these experiences were very unique in some ways and quite common in others.

So I wrote the book from that perspective, at least at the beginning: that of a child trying to piece together the reality of the changing world around him; because that’s how I experienced it. There were mysteries. What is a restaurant? (We’d never been in one). What is a car? A city? And, most devastatingly, what is a family? Because we simply didn’t know.

And of course we got many things wrong. We were told information about ourselves and our story that was simply untrue. We witnessed violence and we were told we didn’t. We were put into what was essentially an orphanage and we were told it was a “good school.” There was no one to tell about the fear and loneliness we felt because it was all so routine. Everyone was there with us. All the kids were separated from their parents at six months old. Some Synanon kids didn’t see their parents for months, years at a time.

I think anyone who claims to be too sure about the facts of their childhood is stretching the truth. Memory creates a fog, time stretches certain moments, compresses others, colors everything. It’s dangerous (or at least a form of basic bullshit) to pretend to be too sure about it.

So when writing about lived events from childhood, there are a few ways to engage this fog of memory. One is to come at it head on, to simply state, “my memory is a fog and here is how it comes to me, here are the ways I am interrogating it and here are my conclusions.” I think that’s one effective way to do it. I admire people who do this.

Another way to do it is to give the facts as you understood them, even if they’re wrong, and let the reader follow your journey of discovery. In my book, I say things as a child that are demonstrably wrong. Some of this is the magical thinking of children (at six years old were you absolutely certain you couldn’t fly?), some of it is my wholesale acceptance of what the adults were telling us. I later found that these are the early narratives common in emotionally abusive homes, and I had internalized them already at a young age. We were abandoned, neglected, abused, left in a cult. So looking through the fog of my own memory, I realized how much these early narratives defined me, even though I logically know they weren’t true. In the book, I just present it whole, the way it came to me in my life: like a mystery I couldn’t quite fathom that I had to piece together over a lifetime.

Did writing Hollywood Park change any of your perceptions about your family? Did you come to any insights that surprised you?

I came to understand my brother much better. He was always the angry one. I was the good one. Those were our roles. He resisted all parenting, broke all rules, was the classic “scapegoat” child one reads about in books on dysfunctional families. He became an alcoholic at thirteen, a drug addict by 15 and eventually moved on to heroin, crack, you name it. I think I resented all this as a child. But revisiting it with the perspective on NPD (and the fact that we were orphans) I came to empathize with him. His story as a child is so incredibly sad. He was made into an orphan at six months old and lived alone as one until he was 7. It’s like he was just abandoned on a playground. We escaped the cult early one morning with a woman we hardly knew (people told us she was our “mom” but since no one knew their parents, the term didn’t have any particular meaning) then spent awhile on the run, trying to avoid the violent goons that Synanon sent after the “dirty fucking splittees” who left. We saw our kind roommate get beat nearly to death by men with clubs from the cult. We then ran away to Oregon where we lived on government assistance and killed rabbits for food. We never had any therapy. No one ever asked us how we felt about anything. We were treated as ancillary, along for the ride with no feelings of our own.

So, yeah, he was mad. Of course he was mad. He had every right to be mad. It was probably healthier for him to just express his anger than what I did which was to try to overcome everything by being that “superchild,” the caretaker one reads about in those same books about dysfunctional families.

His journey took some amazing turns and now, as men, I admire him so much. Here he is this great guy, a great father and friend with a successful business. He really worked hard for that. I’m so proud of him and in awe of his journey. When I look back at the things he said to our parents when we were young, the anger and criticism of our predicament he expressed, my only thought is: “This kid is speaking the fucking truth.”

The book paints a picture of a very complicated relationship with your mother. What was it like to revisit those memories from your childhood?

It was difficult, eye-opening, a struggle. I think my mother really tried her best to outrun her demons. It just didn’t work. She joined the commune which became a cult out of a deep (and I believe, sincere) desire to change the world. She was part of the free-speech movement at Berkeley, attending sit-ins and marches and eventually taking the final step of trying to create a utopian society in Synanon. Like so many of the most breathless dreams of the sixties, it all came crashing down, spectacularly so, in the case of Synanon with its devolution into mind control, child abuse, paranoia and violence. So again, it felt like growing up in the wreckage of something, in this case the failed dreams of the sixties, to be broke and alone and hiding out in some backwater place in Oregon raising rabbits and eating government cheese to survive. “Thatasshole Reagan,” the enemy from her free speech days, became president. We lost. Then we retreated. That was the feeling.

It’s hard to speak publicly about these things because a part of me will always feel defensive of her, like I have to guard her the way a boxer guards a broken rib. Yes she caused us a lot of pain but I truly don’t think she did it on purpose. Just because a parent struggles with mental illness, it doesn’t mean they ever intended to hurt their children. And I don’t believe she intended to hurt us.

Having said that, writing about this time helped me to unpack the false narratives I’d been taught about our lives. We were unsafe, unheard, neglected, angry, sad and constantly being told a story about her life instead. That she was a perpetual victim. That our value as human beings revolved around our ability to be caretakers of her (at least for me) and later, to become something “important” that she could brag about. I later learned that these precise dynamics are common among the children of people with narcissistic personality disorder. It was a relief to learn this as an adult: that these relationships between people with NPD and their children hew to very specific patterns. It was a eureka moment to discover it, to give this vague and troubling thing a name. I read other people’s experiences and said, holy shit, there, it was exactly like that.

Part of the problem, I think, is that we don’t, as a society, have a language for NPD. We have language for depression and schizophrenia, addiction and anxiety. But NPD and BPD (borderline personality disorder, which is related), these fairly common disorders which create relationships without empathy, tend to fly under the radar.

If you’ve been hurt by a parent, a part of you always wishes that the parent will someday see it, truly see the pain they caused you, and apologize. It’s a childish wish, I know, and completely beyond the ability of someone with NPD. (People with NPD are simply uncapable of self-reflection in this way.) But I’d be lying if I said despite everything, the child in me wouldn’t want her to read the book and say, “My God, I had no idea. I am so sorry.” The adult in me knows that’s never going to happen.

Although you’re known as the front man for Los Angeles-based rock band The Airborne Toxic Event, you started your career as a fiction writer and journalist. Did you always know you were going to write this book?

No. When I started the band, I knew my writing was going to be put on hold. People would sometimes tell me to write on tour. But living in a bus for 10 years is not a particularly good way to write. It’s all just so disorienting. You’re in Cleveland, you’re in Tokyo, you’re in Kalamazoo. Life on the road feels like a collage, like a fever dream. So when my dad died and my life just kind of fell apart, one of the odd side effects was that I finally had some time. I told the guys I needed a break from the road and I just shacked up with my wife and wrote in my basement for

three years.

What do you want people to take away from Hollywood Park?

I guess there are some fancy things I could say about emotional resonance, landscapes of the mind and the sob in the spine of the artist-reader (that’s how Nabokov put it) but any first-time author is lying who doesn’t simply say, I really hope people like my book.