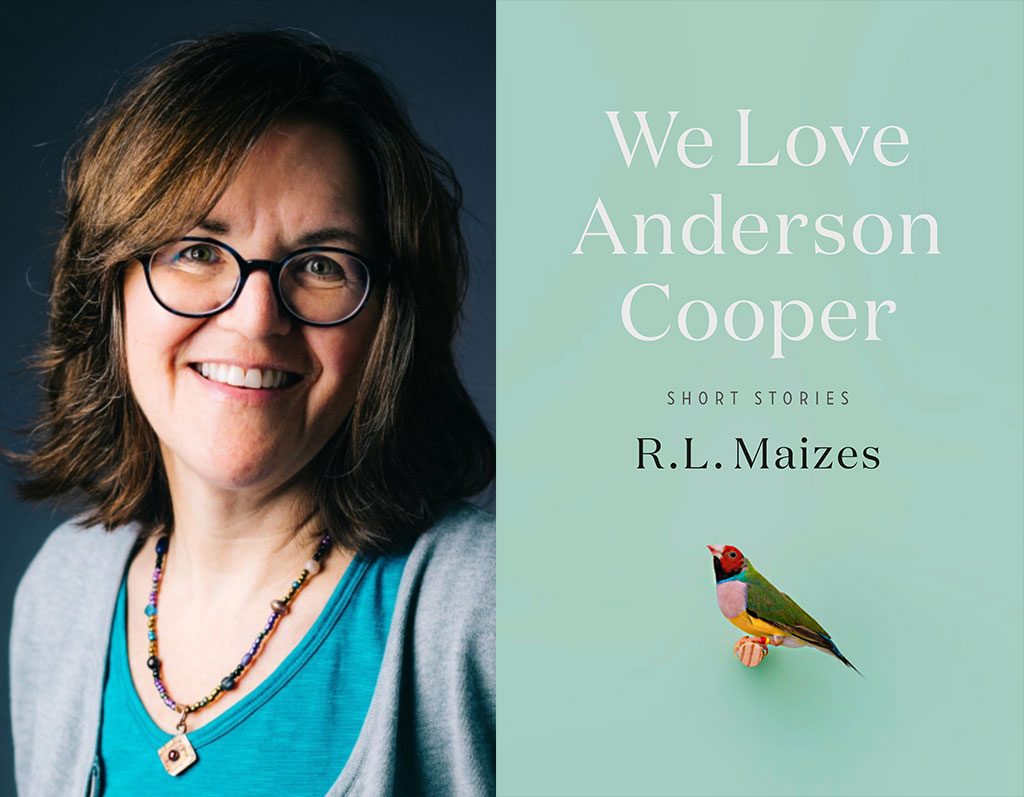

R.L. Maizes’ short story collection We Love Anderson Cooper (July 2019) is compassionate, funny, and deeply relatable to anyone who’s ever felt like an outsider.By Erin McReynoldsA young man courts the publicity that comes from outing himself at his bar mitzvah; a Jewish actuary suspects his cat of cheating on him with his Protestant girlfriend; a painter who’s shunned because of his appearance inks tattoos that come alive. Celadon sat down with the author to discuss these unforgettable stories, her writing advice, and what’s next.This is your first book—did you set out to write a collection or did you notice a throughline in stories you’d already written? What’s the newest, and the oldest, story in the book?

The newest story is the title story, “We Love Anderson Cooper.” One of the oldest stories is “Couch,” which I wrote about ten years ago and revised for the collection. My mother was a therapist and the story was inspired by her therapy couch that I imagined made people weep as soon as they sat on it. The story was also inspired by the many therapists—good and bad—I’ve seen over the years. I hope they all buy a copy. That alone would give me a bump in sales.

In assembling the book, I selected stories about outsiders because it’s a theme most people can relate to, especially these days. I think it’s fair to say we’ve all been outsiders at one time or another.

In the collection’s eponymous story, a boy grapples with the decision to come out at his bar mitzvah. In a clumsy, albeit well-intentioned conversation, his mother asks why he felt he couldn’t do it sooner. Is that what you wanted to capture in this book—the clumsiness of good intentions?

The book is full of well-intentioned, but misguided characters, such as the mother who buys her daughter a parakeet to replace her dead father, the tattoo artist who magically remakes his clients’ physiques, and the therapist who lets her clients cry week after week and sometimes sobs with them. Though the characters mean well, they often fail spectacularly. In the stories, humor tempers serious themes.

Animals figure prominently in your stories—a man grows jealous of his cat’s affections for his girlfriend; a grieving daughter detests the bird her mother gives her. What do animal characters allow you to do that you can’t do with humans?

Structuring conflict around animals allows me to approach classic themes, such as jealousy and loss, from a fresh angle. Take the story about the cat that transfers its affections to its owner’s girlfriend. The woman wouldn’t cheat on her boyfriend with another man; but being seduced by the cat seems harmless to her, though it isn’t. The man’s jealousy over a cat might seem absurd, but it’s no less painful to him. With the cat as the focus, the story can approach infidelity in an offbeat manner. In the story about the bird, the main character has lost her father, and in his place her mother has given her a parakeet. It’s a pretty rotten deal, and one that compounds the daughter’s feelings of loss. She acts out in a way that works for the story only because it’s directed against the bird. I won’t say more because I don’t want to spoil the plot.

These characters are all so distinct and memorable—do you feel like you might follow one or two around in a novel?

I don’t have plans to expand any of the stories into a novel. The characters in the stories have gotten into trouble and have attempted to get out of it. They’ve suffered as much as they’re going to suffer at my hands. Readers are welcome to imagine the characters’ future lives. I hope they do. The novel I’m writing shares a theme with the stories—the protagonist is an outsider—but the characters in the novel are new.

Do you have any advice for writers who have been at it a while and may be discouraged by trying (and sometimes failing) to get published? Any guidance for those starting out?

I had a writing teacher who said he didn’t know anyone who stuck with it who didn’t ultimately have success. So, to those who have been at it for a while, I would say, keep writing. Focus on the joy of creation, because without that, there’s no reason to write. It will help you tolerate the pain of rejection that accompanies writers throughout their careers but is—with any luck—interrupted by periods of success.

For those who are just starting out, I would say, write a lot. Read a lot. Find teachers or other writers whose advice resonates with you to critique your work. Try to avoid all the bad advice that’s out there, which is any advice that isn’t given in a helpful spirit or doesn’t resonate with you. Make friends with fellow writers. They’re your lifeline on the sometimes airless planet known as submitting your work.

Your novel comes out next year. What’s it about, and how do you approach writing a longer work versus writing a short story?

The novel is about an animal empath who robs houses to pay her father’s legal bills after he’s arrested for burglary and assault. My process for writing shorter or longer work is similar in many ways. Six out of seven days a week, I make time to write. I draft and revise until the plot and prose become too familiar, then I put the work aside or send it to a trusted reader for feedback. One difference is that I never outline short stories. I started the novel without an outline, which gave me the freedom to follow the characters wherever they wanted to go. But after the third draft, I realized I needed an outline to track all the plots and subplots, and even the passage of time so I didn’t describe it as snowing in August. The novel often strays from the outline, but the roadmap is there when I need it.