We lived high above the rest of the world. Our town sat in the narrow aperture between mountains, the mountains forested, the forests impenetrable. A cool, damp place: ferns pushing up between rocks, moss on roofs, spiderwebs spanning the eaves, their strands beaded with water. Every day at dusk the clouds appeared, gathering out of nothing and thickening until they covered us with their beautiful, sinister white. They settled into everything, wrapped around chimneys and hovered over streets and slid among trees in the forest. Our braids grew damp and heavy with them. If we forgot to take our washing off the line in time, it became soaked all over again. We retreated to our houses, flung open our windows and invited the clouds in; when we breathed in they filled us, and when we breathed out they caught us: our dreams, our memories, our secrets.

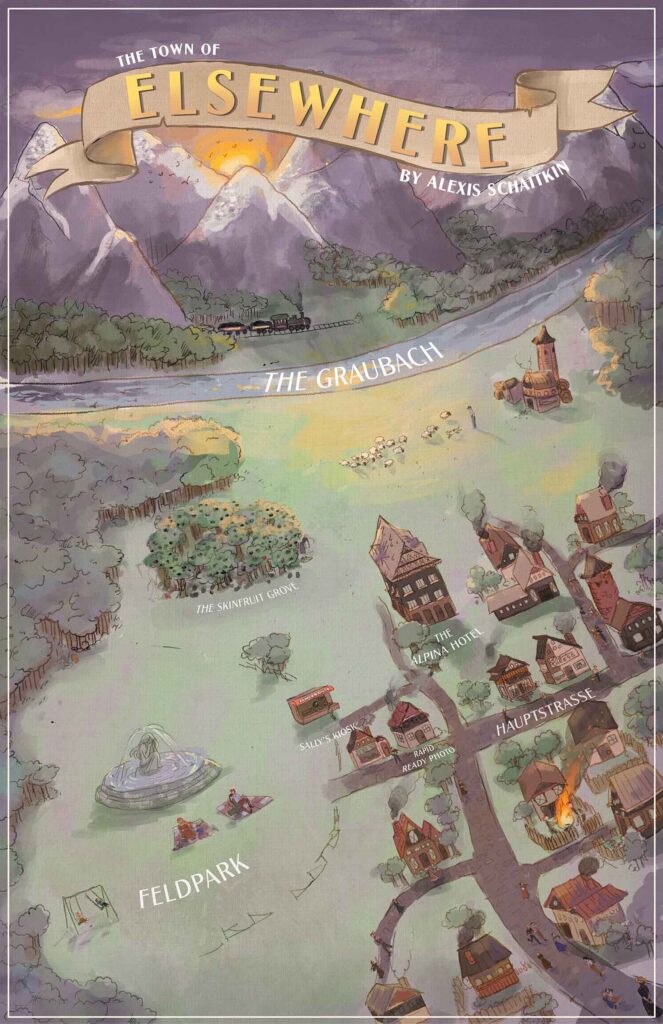

We didn’t know who cleared the forest and established our town, or how long ago. We could only guess at our origins by their traces, which suggested that whoever built this place had come from far away. Our streets and park and river carried names in a language we did not speak. An earthen embankment stretched along the river to protect us from floods, but this was unnecessary here. It never rained enough for a flood; we received only gentle showers of predictable duration. Our houses and shops featured steeply pitched roofs built for snow, though it didn’t snow here. We had no seasons; our climate was always temperate and pleasant. What brought them to such an isolated location? Was there a time when people lived here as they lived elsewhere? Or was this place afflicted already, and did the affliction draw them here?

I find it difficult to determine when, as children, we came into an awareness of the ways our affliction set us apart. Even when we were too young to understand it, it showed up in our games and make believe. Young boys could often be seen at the edge of the forest, huddled around piles of sticks and leaves and paper, holding stolen matches to the tinder until it caught and watching it burn. Young girls concealed themselves, crouching among the foxgloves in dooryard gardens, burying themselves under heavy quilts in their parents’ beds, playing at being gone. Ana and I played ‘mothers’ constantly. We fed our dolls bits of moss and lichen and swaddled them in scraps of muslin. We crept to the edge of the skinfruit grove and stole fruits off the ground, rubbed the red pulp on our dolls’ cheeks for fevers and healed them with our special ‘tinctures,’ river water from the Graubach. Our mothers were a pairing and Ana and I had been inseparable since we were born. We lived right across from each other on Eschen, one of our town’s short backstreets. Our bedroom windows faced each other, and she was the first person I saw when I woke up and the last person I saw before I went to sleep. We would stand at our windows and press our hands to the panes, and I could swear I felt her hand against mine, like we had the power to collapse the distance between us. We used to tell people we were twins, one of those obvious lies small children tell; everyone in town knew us, knew our mothers, besides which we could not have looked less alike. Ana was the tallest girl in our year, everything about her solid: her legs strong and quick, braids thick as climbing ropes, big blunt eyes that stared at whatever they pleased. I was scrawny enough to wear her hand-me-downs, my braids so puny they curled outward like string beans, eyes cast up, down, away, never settling anywhere too long.

My doll was Walina and Ana’s was Kitty. Such dirty things. We wiped our noses in their matted hair. We filched dried skinfruit vines from our mothers’ piles and wove thorned cradles that scratched their limbs. We slipped our silver hairpins from our braids and used the sharp points to prick each other, then pressed the blood to our dolls’ cloth torsos to give them pox. Once, we licked what remained of the blood off one another’s skin, giggling nervously because we were do ing something we shouldn’t. We were supposed to keep the points of our pins clean, held fast in our braids, until we were grown and ready to prick a man’s skin. Ana’s blood left a hot tang in my mouth I tasted for days.

Often, we abandoned our dolls in the grass overnight. When we fetched them in the morning they were soaked, heavy as real babies. They stayed damp for days. We pressed our faces to them and breathed in their thrilling stink, like the wet pelts of goats in the forest. Sometimes we lifted our shirts and pressed our nipples into their rose bud mouths, and I imagined sweet, blood-warm milk flowing from me into Walina. We cared for our dolls wretchedly, but we loved them. I wondered later whether we had sensed that our mothers would go, and if this was what compelled us to treat our dolls as we did; or whether, somehow, it was our mistreatment of them that summoned the affliction to our mothers.

When Ana and I were out and about in town, we tried to watch the mothers like the grown-ups watched them and like the mothers watched each other, but we didn’t really know what we were supposed to be looking for. We saw them alone and in their threes. At the Op Shop, we watched them try on dresses and slide gold hooks through the holes in their ears, studied them studying themselves in the mirrors. We pressed our noses to the windows of the dining room at the Alpina during afternoon tea, saw their hands bring the hotel’s blue china teacups to their mouths, their lips move with silent gossip and speculation between sips. We lurked at the edge of the skinfruit grove when they gathered the fruits in their baskets and pulled down the spent vines. Sometimes a mother split one of the black fruits open and ate it right there, sucking out the red membrane and cracking the white teardrop seeds with her teeth. The mothers said the fruit was like nothing else. I tried to imagine it, but I couldn’t; my mind doubled back on itself when it tried to think up a taste it had never tasted. We saw the mothers on their porches, snapping the thorns from the vines and weaving their baskets. We saw how they swayed with their babies in their arms, side to side like metronomes holding time for a song only they could hear. Sometimes a mother caught us staring. Ana would thrust out her tongue at her, and a feeling would come over me like the mother saw through me to everything I could not yet imagine I would do.

It was Ana who taught me to eat dirt on the mornings after a mother went. We did it when everyone gathered on the lawn. There was so much happening then, with the proceedings getting underway, so it was easy to slip off unnoticed. The rest of town was deserted on those mornings. We had it all to ourselves. We ate soil from pots of dancing lady on porch steps. We pulled grass from the playing fields at Feldpark and licked the dirt that clung to the white roots. In the forest, we coated our tongues with the dirt that hid beneath the slick black leaves on the ground. Ana never explained why we did this and I never asked. I was always content to go along with her schemes. When I ate the dirt, I imagined a forest growing inside me, every leaf on every tree the same as our forest. We were binding ourselves to this place, I understood that much. But I didn’t know whether Ana saw our little habit as preventative, or whether she hoped in swallowing the earth to make something dark take root inside her, to feed it and make it grow.

Aside from ‘mothers,’ the only game we played with any regularity was ‘stranger.’ We had never seen a stranger ourselves, so naturally we found them fertile ground for make-believe. The last person to stumble upon our town from elsewhere had come before we were born, and nobody ever talked about her. True, we had Mr. Phillips, but that wasn’t the same. He had been our town’s supplier our whole lives, bringing goods to us four times a year; he came from elsewhere, but he wasn’t a stranger.

We played in the forest, taking turns with who got to be the stranger and who got to be herself, coming upon them. We each had our own approach to playing the stranger. I imagined them wretched and cowed. I smudged dirt on my cheeks and pulled my hair out of the tight braids my mother must have woven. I moved erratically, darting this way and that, froze like a stunned deer at every snap of a twig underfoot, as if terrified by my own presence. When Ana came upon me I reached out to her and whispered, ‘Help me. Help me.’

Ana’s version was violent. She thrashed through the forest, eyes feral as the eyes of the goats. She bared her teeth at me and drew her hands into claws and made to scratch me, and I tried to make my mind forget that it was Ana, who I had never not known, and sometimes I got close, I saw only her wildness and the emptiness behind it, and I imagined that, having seen a stranger, I would never be the same.

It makes sense that we approached it so differently, because we had only the most elementary understanding of strangers. We knew only that the ones who had come to town in the past had all turned out to be disappointments, painful lessons in what life elsewhere made people into. Their lives were ruled by a simpler, thinner calculus. They sought only obvious pleasures and the avoidance of pain, and they would do anything to achieve these ends. They couldn’t help it. They didn’t have our affliction so they could not learn what it taught us, did not possess what it gave us.

But when a stranger did come, she was nothing like either Ana or I had imagined. This was at the end of upper year, when I was sixteen. By then, Ana and I had not been a pairing for a long time. She had severed our tie suddenly and brutally after our mothers went. From then on the memory of our friendship lived inside me like a potent dream, difficult to believe it had ever been real.

The stranger arrived in the afternoon, when I was working my shift at Rapid Ready Photo. It was my father’s store. He took the formal portraits for everyone in town: school, wedding, newborn. He spent most of his days in the darkroom in the back of the shop and I worked the register after school. Like the other shops, we were never busy; we lacked the population to be. I spent my shifts doodling in the margins of my notebooks instead of doing homework. I practiced violin. I took coins from the register and bought fruit candies from the crank vend at the front of the store, let them lodge in my back teeth and worked over the rough sugar with my tongue. I spun myself slowly around on my stool, trying to match the speed of my revolutions to that of the fan overhead and watched the shop swirl around me. This is what I was doing that day when a blur out the shop’s front window caught my eye. I slowed to a stop, looked out and there she was, way down Hauptstrasse, coming up the sidewalk. In our girlhood games, Ana and I had imagined strangers as extreme figures. But this woman appeared almost ordinary. Still, I could tell straightaway, when she was still quite far off, that she wasn’t one of us. It was the way she carried herself, a difference in bearing, subtle yet profound. She held herself very erect, yet this had the effect of making her appear not haughty but guarded, vulnerable, like a small bird puffing itself up. She wore a dark crepe dress with small white flowers and soft brown boots on her feet. On her head, a straw hat with a band of black ribbon. She hadn’t bothered to tie the ribbon under her chin; it flowed down her back against her hair. She carried a leather valise, which she let knock against her side as she made her way up the street, peering in the shop windows. A camera hung from a strap around her neck, so I should not have been as surprised as I was when she reached our shop and stepped inside.

She approached the counter with her eyes downcast. When she reached it, she stood straight and still before me, though even in stillness a twitchy energy escaped her. I waited for her to speak, but for an uncomfortable amount of time she didn’t, she just kept her eyes on the floor. I wondered if shops worked differently elsewhere. ‘Can I help you?’ I asked gently.

She looked up. We stood there, so close together, and stared at each other. When I had imagined coming upon a stranger as a child, it was seeing them that mattered, and letting their strangeness operate upon me. Yet it turned out what mattered most in that first encounter wasn’t seeing her but being seen by her, a person who didn’t know me. Beneath her gaze I felt my self sweep cleanly away, like flotsam borne off on the Graubach. Briefly, ecstatically, I wasn’t me at all, but anyone and no one.

She looked at me with a sort of labored smile, like she was trying hard to show she wasn’t hostile, or maybe like she feared I might be hostile. It was my first lesson in the stranger, that her every action, down to her tiniest movements, would suggest two opposed interpretations.

‘A roll of film, please.’ She spoke in the softest voice, like her throat was too clenched to let any more sound escape.

‘So what brings you to our town?’ I asked with an encouraging warmth as I fetched the film from a hook on the wall. It seemed she hadn’t yet determined what kind of place this was, and I wanted to reassure her she had nothing to fear here. But my question seemed to have the opposite effect. A frightened look came over her, like her life had primed her to hear even a simple, friendly question as an intrusion, maybe even a dangerous one.

‘Holiday,’ she said unconvincingly. She had a habit, I was coming to notice, of stroking the black ribbon that hung down from her hat as if it were a creature she was trying to soothe. She must have been riding the train and seen our supply road winding into the mountains and decided to hop off between stations. I wondered what had happened to her elsewhere for her to end up here all alone and in such a state, although perhaps it was usual for a woman to be so skittish and agitated there.

As I rang up her film, she surveyed the shop.

‘If you need something you don’t see here, we can always put in a special order with Mr. Phillips,’ I said. ‘That is, if you’ll be staying awhile.’ I hoped she would tell me how long she planned to be with us, information I was desperate for personally and which would make me in-demand at school the next day. But it was like she hadn’t even heard that part of what I said.

‘Mr. Phillips?’ she asked.

‘Our supplier. He can get you anything. You just tell him what you need and when he comes back he’ll have it. You’d like Mr. Phillips. He’s a consummate professional.’ I cringed at myself, parroting some thing I’d heard adults say. It was true though. He performed his duties with diligence and discretion, bringing our supplies and taking the baskets our mothers wove back to the city, where he sold them without telling anyone where they came from. We trusted him not to speak of us elsewhere. He didn’t pry into our lives, nor did he burden us with his troubles. We knew it must be painful for him, the glimpses he got each supply of the beauty of this place and the force of our lives here, but he didn’t let this show. He had been our supplier since the previous supplier, another Mr. Phillips, stopped coming when my father was a boy. He was so buttoned up about his work that we didn’t even know whether the prior Mr. Phillips had retired or passed away, or whether our current Mr. Phillips was that Mr. Phillips’s son, or if the name was merely a coincidence, or if this Mr. Phillips had taken the name of the other. According to the adults in town, the prior Mr. Phillips had been a different sort, frantic and addled, always rushing, his papers in shambles, and he often got orders wrong, or tossed our baskets into the freight car in so slapdash a way that some were inevitably damaged and rendered unsalable. Though some of the oldest adults said he hadn’t always been that way, had in his prime been nearly as adept as our current Mr. Phillips, his suits pressed instead of rumpled, hair hard and glossy, not the gray tumbleweed it became. This was how life elsewhere worked upon people. They accumulated years rather purposelessly, so that as they aged they did not unearth their deepest, truest selves but, on the contrary, grew increasingly dispossessed of themselves.

The stranger laughed, amused by what I’d said about Mr. Phillips being a ‘consummate professional.’ I blushed.

‘Are you alone here?’ she asked.

‘My father’s in the darkroom.’

‘Just the two of you?’

I nodded, and blushed again. It was my first time ever talking to someone who didn’t know our situation, and it was embarrassing, even a bit painful, to have to confirm it. It was unusual for a father not to marry again after a mother went, and it was looked down upon. Ana’s father had remarried in less than a year, and he and his new wife had three more children. But the stranger didn’t know any of this, and to my relief she just smiled in response, at once piercing and vague.

When I told her how much it was for the film, she opened the va lise, removed a change purse, and stacked the coins on the counter. I froze for a moment when she did that, but I quickly pulled myself together. I didn’t want to make her self-conscious. I used one hand to sweep the stack off the edge of the counter into my other hand and sorted the coins into the register.

‘Well, thank you,’ she said.

‘See you around. I’m Vera, by the way.’ I said it as casually as I could manage.

‘And I’m Ruth. See you around, Vera.’

For the rest of my shift I heard the echo of her strange voice saying my name, Vera, Vera, Vera, until it seemed a foreign, inscrutable thing.

In the coming days, when I told people about my first sighting of the stranger, it was the coins I returned to, how she stacked them on the counter like that. It was such a clear example of the tiny actions that betrayed so much about her and the place from which she had come. In our town, whenever money changed hands, we touched, fingertips brushing briefly as the coins passed from one hand to another. We didn’t only do this with money. We touched whenever we gave or took something, when we shared a sip of our tea with a friend, or picked up a baby’s fallen sock on the sidewalk and returned it to his mother. Even Ana, who was so often cruel to me, would never just set her coins on the counter when she made a purchase at Rapid; we let our fingers brush, a touch absent of personal rancor because it wasn’t personal, it was communal, hundreds of small touches threaded through our days like the unconscious way you touch your own body. The stranger had never had this and she didn’t even know she hadn’t.

That night as we ladled stew into bowls, brushed the tiny pearl teeth of children and sang them lullabies, we felt the stranger’s presence; it seemed we did these things for her, as if, while our town’s population had increased by a single person, we had also doubled, become both ourselves and the sight of ourselves, now that we had a stranger to see us.

Once our children were asleep, the lovemaking began, bodies pressed together under heavy damp quilts. Husbands and wives were together that night not like people who had never not known each other, but with the passion and hunger of strangers. A husband saw not his wife with the pink scar their son liked to stroke and call mama’s worm, felt not the fingertips callused by her instrument, smelled not the frying oil in her hair, talc on her thighs, but a mystery. The unknown of her rose above him, the precious things he knew of her reduced to almost nothing.

• • •

The atmosphere in town the next day was festive, everybody eagerly sharing news of the stranger. Sally made sure we all knew she’d been the first to see her. Sally ran the concession kiosk at the entrance to Feldpark, selling tea and shortbread and griddled sandwiches, and from that vantage point she had a clear view of the supply road’s final steep stretch. She claimed the stranger told her she had never seen a more beautiful place. While we were happy to hear this, we did not want to ascribe too much significance to Sally’s report. She was a shallow and unserious person, prone to embellishment, and she loved nothing so much as to be an authority on a subject of collective interest. We teenage girls often walked away giggling after we made our purchases from her. She was old enough that her hair was silver, and we couldn’t get over the fussy way she styled herself, in lacy blouses and ruffled skirts, or her hair, which she wore in ringlets like a birthday girl. The boys our age loved to get Sally going, to draw out her most ridiculous behavior, which was easy to do. Once, Di, Marie, and I were behind Nicolas in line, and we heard him tell Sally her shortbread was the best in town, even better than his mother’s. He leaned across the counter and whispered, ‘Let’s keep that our little secret, okay, Sally?’ Like clockwork, she fluttered her eyelashes and tucked an extra short bread into his waxed paper packet, and as she passed it to him and their fingertips brushed, she whispered, ‘Our secret.’ In fairness, it wasn’t just us teenagers; Sally was one of the few childless women in town, and the mothers were always chattering about the way she badgered them with questions and pounced on the tiniest scraps of gossip about their lives, desperate to matter any way she could.

In the caf at lunch that day, everybody was talking about their first sightings. I told Di and Marie how the stranger had set her coins on the counter. Di, Marie, and I had been a threesome for years. I had secured myself to them shortly after Ana ended our pairing. We made for a somewhat unnatural threesome, frivolous Di and rigid Marie and quiet Vera, though like all threesomes we did everything together. Di told Marie and me she’d noticed the stranger wore no jewelry whatsoever in her hair. Marie recounted her sighting with particular relish. She had been practicing her cello by the parlor window when she looked up from her music and saw the stranger passing on the sidewalk. At first, she thought she was the woman from the framed illustration on the wall of the ice cream parlor. ‘Isn’t it funny, the tricks our minds play?’ Marie said. It turned out Marie was in good company. Many of us mistook the woman, at first, for someone whose image we had seen before, in a painting or on the packaging for some product or other.

Stories began to circulate among us uppers of the most memorable sightings. Jonathan had come quite close to her. He had gone out to skin and clean the rabbit his mother would cook for supper. He had slaughtered it the day before and was lifting it from the basin of salt water, now dark pink, on the front porch when she walked past. He said the skin on her arms was all gooseflesh; she must have been so accustomed to the sweltering lowland heat that her body didn’t know what to make of our refreshing climate.

Liese said that outside of her house on Gartenstrasse, the stranger had paused to smell the mother-of-the-evening that grew along the fence line. It was the end of the day, when the clouds were beginning to gather and the flowers released their sweet fragrance like an offering. The stranger closed her eyes and her face crinkled in ecstasy, as if she had never before breathed a scent so potent and lovely.

We were wary. Everything we knew of strangers suggested she was not to be trusted. But Ruth seemed harmless; a pathetic figure, not a dangerous one. Over the following days, we learned that she was a creature of habit. Every morning she came down from her room at the Alpina just before eight. We were so pleased that the Alpina had a real guest, one who had traveled to reach it, not just one of our newlywed couples staying in the honeymoon suite. In the dining room, she ate a breakfast of yogurt with stewed fruit. She took her tea with milk and four cubes of sugar, more than even our youngest children, like the only kind of pleasure she could understand was one as rudimentary as sweetness. Next, she walked in the mountains, vanishing from us for hours. She returned in early afternoon, her canvas shoes muddy, shoelaces snagged with burs. The boots she had worn the day she arrived had a small heel; in her canvas walking shoes we saw how slight she was. For the rest of the day she did what might be called poking around, strolling Hauptstrasse and popping into stores to look at this or that. She stroked the supple items in the leather goods shop, marveled at the pastries in the case at the bakery. She stood for a long time on the sidewalk outside the creamery and watched through the shop’s front window as our cheesemaker poured doe’s milk into basins, cut the curds and poured off the whey, pale and translucent as clouds. Her valise had been small and we quickly learned the few possessions she had brought with her. The brown boots and the canvas walking shoes, the dark crepe dress with the small white flowers, a chambray button down and trousers, a gray shawl knit of a flimsy, fragile yarn, the straw hat with black ribbons.

She almost always had her camera with her, hanging from the strap around her neck. This interested us. We really only took portraits, whereas she photographed the smallest things. When we saw her pause to snap a picture, a warm sensation spread through us, the almost erotic pleasure of seeing her seeing us. For all her timidity, the stranger Ruth had a certain power. Her attention drew ours to those details of our town so familiar we had long ago ceased to appreciate them. With nothing but her presence she altered our familiar spaces around her.

Walking along Gartenstrasse at dusk, when the clouds were just beginning to appear, she photographed the mother-of-the-evening she’d paused to smell when she first arrived. The flower grew relentlessly, crowding everything else out. We’d grown sick of seeing it wherever we looked, but now we looked again and saw how beautiful it was, even this, our most bothersome weed, how through the clouds its pale purple petals seemed to glow. In the grove, she photographed the night-dark fruit. She even took a picture of a picture, a sepia photograph that hung in a corridor off the lobby at the Alpina: girls all in a row in front of our stone school. This picture was so old we didn’t know who the girls were or whether they had been born here or had been among the people who first came to this place. They wore matching white blouses with black buttons, skirts to their ankles, braids with the silver pins fastened near the bottom instead of the nape. Their eyes were creepy the way eyes so often are in old photographs. At the end of the row, the smallest girl, much smaller than the others, scowled down at the ground. Her image was smudged, doubled: both her and a faint ghost that seemed to pull away from her. It pleased us that the stranger took notice of this photograph; she could feel our town’s power even if she could not understand it. We believed our affliction began with this smudged, doubled girl, that she became a wife who became a mother who became the first of us to go.

• • •

Admittedly, it was mostly children who believed this about the girl in the photograph. This was owing to a popular legend, according to which a mother on the verge of going would not appear in photo graphs, or her image would be blurred or transparent. Occasionally, an anxious child or a new mother would get carried away with this superstition, a bit compulsive about it, which I would know because they would bring rolls of film to Rapid that turned out to be full of nothing but pictures of the anxious child’s mother, or pictures the new mother had taken of herself in a mirror. They couldn’t stop monitoring, checking to see if it was happening.

Perhaps because of my father’s work, I was always especially compelled by this legend. Some of my earliest memories were of being in the darkroom, its sealed red darkness like the inside of a body. While my father worked I studied the strips of negatives that hung from clothespins on a length of twine, lilting in the airless room as if buffeted by the memories of breezes held in their images. In the negatives, people turned the opposite of themselves: black teeth, bright open mouths, eyes an obliterated white like the eyes of animals at night. The negatives terrified me, and I couldn’t keep myself from looking at them. I watched my father manipulate the tools of his trade, reels and clips and tongs and rollers, working with sober grace, as if his fine-boned hands were mere extensions of his implements, his body one more mechanism in this mysterious craft. Sometimes he held me in the crook of his arm and I peered over the enamel trays, nose near to skimming the chemicals, the vinegar of stop bath so sharp it burned my eyes, and watched as he conjured faces from nothing, summoning them from their burial within the cloud-white paper. How had anyone ever come up with it? Mix this with that, soak this in the other, do all of it in the dark and call forth an image of a person as they were but are no longer. Pluck a vanished moment from the sea of the past and lock it in forever.

When our affliction came for a mother, her going was like unwinding this process: One minute she was here, as solid and real as any of us, the next her body faded, faded, until she vanished into the clouds. Gone. We all knew the stories. A mother woke her husband and told him she couldn’t sleep. He turned on the bedside lamp and looked back at her and . . . nothing, no one. In the middle of the night, a mother went to fix a cup of milk for her child. A few minutes later her husband was startled by the sound of glass shattering. Outside the nursery door he found the shards, warm milk all around, his wife nowhere. A mother nursed her infant in the rocking chair, and a father lay awake listening to the rhythmic creaking of the chair until, abruptly, it ceased, and there was the child, alone in the chair.

When a mother went, we woke in the morning and sensed it. The clouds that took her touched us all, connected us all, an intimacy we had never not known. We felt her vanishing like a thread cut loose, presence turned to absence.

Ana had been beside her mother when she went. She had crept down the hallway in the night and slipped into her parents’ bed. In the morning, her mother was gone. Ana’s arm still bore the imprints of her fingertips; her mother had clung to her until the last possible moment. I woke up that morning to the sound of the screen door across the street slapping shut. I went to the window and there was Ana, standing on the porch, barefoot in her nightie, the silhouette of her clenched body visible through the thin material, hair unbrushed and tangled like our dolls’ hair. She walked to the edge of the top step and unleashed a wail. It seemed to come from everywhere at once, down from the clouds and up from the earth and from inside me, like my bones had all along been tuned to the frequency of that wail and had now been set vibrating by it.

My own mother’s going, just a week after Ana’s mother’s, carried no such story. Three of us went to sleep, and in the morning only two of us were there to wake. I expected our mothers’ fates would draw Ana and me even closer, but I could not have been more wrong. The day after my mother’s going, in the afternoon when the proceedings were finished, I tucked Walina under my arm and ran across Eschen to Ana’s. I had to get away from our house, which was so empty now, my father and I settling already into the silence that was all we knew how to make together. But when I was about to cross the threshold into Ana’s house, she slammed the screen door in my face. She said nothing, only stared at me through the screen with a fury that seemed to steam out of her until I retreated to my own porch to play with Walina alone, which was no good at all; I would never play with Walina again after that. I would never play with Ana again, either. She was still the first person I saw when I woke up and the last one I saw before going to sleep, but now these were only glimpses I caught: Ana stretching her arms over her head in the morning, Ana unspooling her braids at night, and always, Ana turned resolutely away from me, as if determined to expand the distance between us however she could. She didn’t speak to me again until some months after our mothers went, when she had settled into her threesome with Esther and Lu, and then she spoke to me not as Ana but in their unified voice, with which they taunted and teased me for some offense I couldn’t determine. I understood only that I was hated, and that this hate was as strong and intimate as the love that had preceded it. Maybe Ana hated me for the week that separated her mother’s going from mine, that brief, unbridgeable interval when I still had my mother but she no longer had hers. Or maybe it was because, in the wake of our mothers’ goings, when our town combed back through their lives to determine what the affliction had seen in them, why it had chosen them, it was their pairing everyone focused on. Threesomes were standard in our town, while pairings were rare, and a risk: to bind oneself so tightly to one other girl, to build your fate around hers. It suggested a certain heedlessness, and once they went we saw plainly that this heedlessness had been all over their mothering in small but significant ways. One clue about my mother everyone kept recounting was that I often turned up at school with my buckle shoes switched, right shoe on left foot, left shoe on right foot, which gave my appearance an ‘unnerving’ effect. My mother let me put my shoes on myself and she didn’t bother to switch them if I did it wrong.

That might seem too minor to count for much, but that was just it: Our affliction was never not watching us. It saw us more clearly than we saw one another, or even ourselves, so the clues preceding a mother’s going could be the smallest things, so subtle they became visible to us only in retrospect, when her going cast its clarifying light onto her past. Nothing was too insignificant to be a sign. A mother let her children cross the Graubach on the rocks when the water was a little too high, the current a little too swift. At the time it merely struck us as incautious, one of the countless small choices mothers made every day that could end in disaster but didn’t. This was not a judgment. If mothers were cautious all the time, children languished; we understood this. But after she went, we found ourselves returning to that moment: the small children, the slick rocks, water rushing all around, and the mother, looking on calmly from the bank. It appeared differently to us then, no longer the sort of act that any mother might commit, but a moment that contained the singularity of her love for her children, the quality, individual to her as a fingerprint, by which our affliction had chosen her out.

Another mother refused to let anyone watch her infant for even a few minutes so she could bathe or do the shopping, not her sister or her mother or even her husband. She trusted no one but herself. She had always been tightly wound, and we had accepted this behavior as the inevitable and not altogether uncommon result of applying such a temperament to new motherhood. But after she went, we saw clearly the inimitable nature of her mothering, how her love had curdled into obsession.

One mother abandoned her impeccable garden after her child was born. She let the forest reclaim the beds of sweet pea and foxglove, allowed weeds to suffocate the rambling rose along the fence line. Another, who had never shown much diligence about anything before she became a mother, plunged herself into her basket weaving. She kept her child in his swing on the porch for hours while she wove, left the task of soothing him to the breeze instead of rocking him in her arms. One mother was seen yanking her daughter’s braids for a minor offense. Another remained eerily calm when her child spit in her face.

What connected these mothers? Their clues pointed in different directions, indicating recklessness and vigilance, insufficiencies and excesses of love. Love sublimated, love coarsened, love sweetened to rot. The signs preceding a mother’s going were individual to her. They did not add up to something so crude as criteria, as a lesson or a rule. But once a mother went, we saw it, something out of balance in the nature of her love for her children that set her apart. Had she fallen out of balance on her own, and had her fall drawn the affliction to her? Or was she born afflicted, and all along, through her girlhood and her adolescence, her marriage and her pregnancies and, as long as it lasted, her motherhood, had she carried it inside her, and had it worked upon her until there was nothing in her that was not touched by it? We couldn’t say. We knew only that she was no longer meant to be here, that we were not meant to have her, keep her, and her going was the proof of this. Her absence left a cavity, a wound, as if our affliction had opened us to perform a necessary extraction. But like any wound, it healed. For a time, we could still see the traces of it, still feel the tenderness in the places where she used to be. But soon enough a day came when we probed for the spot, and we discovered that we could no longer find it, or even remember how it had felt.

Every year on my birthday, my father took Di, Marie, and me to afternoon tea at the Alpina. We’d been doing this since I was a little girl, when it was what every girl did on her birthday. We were still doing it the year the stranger arrived in town; my sixteenth birthday had been the month before. My father hadn’t put together that I’d outgrown it and I couldn’t bring myself to tell him. Just as when we were girls, Di, reeking of her older sister’s bergamot perfume, snatched up the best pastries before the rest of us could get to them, while Marie put on a prim display, dabbing at invisible crumbs on her lips. I let my tea steep until it was nearly black. The last supply had been several months earlier and the Alpina had run out of the tea sachets Mr. Phillips brought, which came wrapped in pale blue paper with an illustration of tea leaves embossed in gold. For now, we drank a local brew, raspberry leaves and nettle, the loose leaves writhing at the bottom of the hot water like things long-dead, revived. Halfway through tea, as I always did, I excused myself to use the restroom, but I didn’t go to the restroom. I went down the opposite corridor to look at the photograph of the girls. I stared at it, at them, and thought that they were long dead now, all of them except the little one on the end, the blurred runt, who had, perhaps, done something other than die. And I wondered what our affliction had recognized in her, or cultivated in her, until it was all of her.

We circled the stranger. Suddenly, lots of us began taking morning walks into the mountains, and the usually deserted paths became positively crowded. One day in the caf, Marie told Di and me that the previous afternoon, ‘seeing as it was such a fine day,’ she had decided to take her cello to Feldpark to practice the piece we uppers would be performing at the next recital, and the stranger ‘happened to be there taking her photographs’ and had complimented her playing. Di had taken to wearing a straw hat from her sister’s bureau around town, an obvious ploy to get the stranger to remark upon their similar taste. I spotted Ana, Esther, and Lu sitting on the bench below the stranger’s window at the Alpina, gossiping and laughing loudly at regular intervals to show what a fun time they were having. Mothers could often be seen pushing prams down the sidewalks of Hauptstrasse, our principal commercial street, during the afternoon hours when Ruth poked around. Ruth smiled at the babies and sometimes said something like ‘Precious’ or ‘How adorable’ to the mothers, and the mothers thanked her politely, though the vague, aloof quality of Ruth’s smile and these rather vapid things she said only confirmed how limited she was, this woman who was old enough to be a mother but was instead here all alone. Husbands lingered just outside the stranger’s vision in late afternoon, and when the clouds began to gather they approached her as if they just so happened to be passing by and offered to escort her back to the Alpina. They were the most discreet in their circling. They didn’t want their wives to suspect the way the stranger was working upon them. They hardly understood it themselves. At night during lovemaking, when wives removed the silver pins from their braids and pierced their husbands’ skin, the husbands had begun to imagine it was the stranger doing this to them.

I circled her like the rest of us. I was always trying to encounter her, and our town was small enough that often I succeeded. I followed her into the grocery and studied the contents of her basket. Crackers, a sewing kit, a jar of olives. I hated olives, but after seeing them in her basket, I purchased a jar. That night I locked my bedroom door and ate them one at a time; I chewed slowly and methodically, sucked the oil from the fruits, brine like salt water for rinsing a sore throat, and spat the pits into my palm, trying to make them taste to me the way they must to her, like my mouth was strange to me, like it was hers.

I slipped out during my shift and went to Feldpark and sure enough there she was, on one of the benches that surrounded the fountain with the statue of the crying woman at its center. I sat on the bench next to hers and pulled out of my book bag the sheet music for the piece for the next recital. I pretended to study it intently, though really my focus was all on Ruth. I wanted so badly to engage her, but I didn’t want to seem intrusive or desperate, and to my delight it was she who spoke to me.

‘What’s that?’ she asked.

I told her the title of the piece. ‘It’s the name of a river elsewhere,’ I explained. It said so in a brief introductory note at the top of the music. The piece was meant to evoke the journey of this river, which started as a small mountain spring and flowed past the village where the composer had lived, or perhaps lived still, before emptying into the sea.

‘Is that so?’ She looked amused. It occurred to me that this river might be well-known elsewhere, in which case my attempt to appear knowledgeable had actually achieved the opposite.

‘Yes,’ I said. ‘Someplace far from here. A place with seasons.’ I couldn’t help it, I wanted her to know we knew things about the rest of the world. We may have lacked some of the things they had, their films and magazines and periodicals; our library contained just what was useful, picture books and learn-to-reads for small children, arith metic and medical and botany texts, but that was our choice. Mr. Phillips would bring us anything we asked for. If we wanted a novel, or a book of history, or a popular film and a projector to watch it on, all we would have had to do was ask and at the next supply he would have it, but we didn’t. What could the stories and histories of people elsewhere offer us? Only their music, wordless, was of any use to us.

‘I came here from a place like that,’ she said.

I got shy then. Mr. Phillips never spoke to us about elsewhere, and while I supposed there was no rule against it, and pleased as I was that she had confided this in me, I couldn’t help but feel she was telling me things she shouldn’t, and I didn’t know how to respond.

‘You’d love to see the seasons,’ she continued.

Luckily, the clouds had started to come out by then, creeping among the trees and spreading over the fields. I looked at them pointedly. ‘We should probably be going.’ I gathered my things and hurried away.