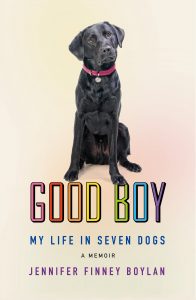

In her New York Times opinion column, Jennifer Finney Boylan wrote about her relationship with her beloved dog Indigo, and the tearjerking column went viral. Her memoir Good Boy uses that column as a springboard to show how a young boy became a middle-aged woman – accompanied at seven crucial moments of growth and transformation by seven memorable dogs.

Introduction

I took her picture one sparkling autumn day, as she stood in our dirt road waiting. There was a bright red maple leaf on the ground.

A year later, I held that photo in my hands as the tears rolled down. An Eva Cassidy ballad, “Autumn Leaves,” played on the radio. It was an old sad song.

My children had been twelve and ten back in 2006. Our family had been through a wrenching couple of years. And yet we’d emerged on the other side of those days still together, the four of us plus Ranger, the black Lab. Our lives revolved around that dog and each other.

But we worried that Ranger felt puny when we weren’t around. Sometimes we arrived back at the house to hear him howling pite-ously. It was heartbreaking, his loneliness.

Then, someone emailed us about this dog named Indigo. She’d had puppies a few months before, and now she needed a home. Were the Boylans interested?

The Boylans were.

Indigo joined us as Ranger’s wing- dog. When she first stepped through the door, her underbelly still showed the recent signs of the litter she’d delivered. Between the wise droopy face and the swinging dog teats, she was a sight to behold.

She had a nose for trouble. On one occasion, I came home to find that she’d eaten a five- pound bag of flour. She was covered in white powder, and flour paw prints were everywhere, including, incredibly, the countertops. I asked the dog what the hell had happened, and Indy just looked at me with a glance that said, I cannot imagine to what you are referring.

Time passed. Our children grew up and went off to college. I left my job at Colby College in Maine and joined the faculty at Barnard. My mother died at age ninety- four. The mirror, which had reflected a young mom when Indigo first barged through the door, now showed a woman in late middle age. I had surgery for cataracts. I began to lose my hearing. We all turned gray: me, my spouse, the dogs.

That summer, I took Indigo for one last walk. She was slow and unsteady on her paws. She looked up at me mournfully. You did say you’d take care of me, when the time came, she said. You promised.

She died on an August afternoon, a tennis ball at her side.

Sometimes, in the weeks that followed, I’d find myself searching for her, as if she might be sleeping in one of my children’s empty bedrooms. But she wasn’t there.

What was it I was looking for, as I poked around the house? Was it really the dog I’d lost? By the time you’re in your fifties, a lot of things have flown. You learn to make your peace with ghosts, but it’s an uneasy truce, at best. I’d sit in my children’s bedrooms now and again and get all mopey about the fact that they’d become adults so swiftly. Here were the talismans of their childhood: finger paintings from pre- K, an old soccer ball, college diplomas.

The rooms reminded me of a photograph I’d once seen of the tomb of Tutankhamun, with the relics of the boy- king’s life— a golden mask, an ancient checkerboard— strewn around the burial chamber. They lay where they’d been left, three thousand years before.

__

I’d been their mother for seventeen years, but for years before that I’d been a father, a boyfriend, a child. I had never regretted coming out as trans, living in the world without shame or secrets. But there were times when I remembered my younger self the way you’d remember a dear friend you’d lost, for reasons you no longer quite understood. Where was that “boy,” that adorable nerd who’d spent his days sitting on the banks of a stream in Pennsylvania, fishing for brook trout? I wondered, sometimes, what had become of him. Would it be neces-sary, in the days to come, to refer to him only in scare quotes?

My days have been numbered in dogs. Even now, when I try to take the measure of the people I have been, I count the years by the dogs I owned in each season. When I was a boy, for instance, I had a dalmatian named Playboy, a resentful hoodlum who loved no one except my father. Later, as a hippie teenager, I had another dalma-tian, a mournful, swollen creature named Sausage. While I was off at Wesleyan becoming insufferably cool, my sister brought a mutt named Matt home from Carleton, a dog whose insatiable sex drive and accompanying disregard for the rule of law made it abundantly clear that he was determined, as they say in Ireland, to live a life given over totally to pleasure. Still later, during my years as a nascent hipster in New York, my family acquired a Lab named Brown whose only true devotion was to eating her own paws, a pastime that obsessed the dog as if her feet were a rarity more succulent than clams casino. In my thirties, as a young husband, I adopted a Gordon setter named Alex, a wise soul who stood watch over my wife and me right up until the day our first child was born. And then, as a father, I shared a house with Lucy, a retriever/chow chow mash- up who wasted exactly zero time in making clear her utter contempt— for me, for our children, for all of us. We’d come home each day to find the dog in a state of cynicism and disapproval. Ohh, she’d say, just like Tony Soprano’s mother. Look who calls.

It was Lucy who was on duty the day I finally came down the stairs in heels. She looked me up and down with exhaustion. Ugh, she said. I wish the Lord would take me now.

Actually, a lot of people reacted like that at first, including many of the men and women I had loved most.

When we talk about dogs, it is not uncommon for people to say things like They love us unconditionally! Their hearts are so pure! But to be honest, I have rarely found this to be the case. When I was a boy, for instance, there was a German shepherd named Gomer who lived on a farm near our house. Most of his days were spent at the end of a heavy iron chain. If he’d been given the option, it was clear enough: Gomer would have torn me apart like a Walmart piñata. The only thing unconditional about Gomer’s feelings toward me was his bottomless hate.

But his owner, Joy, saw in him an adorable rascal. Who’s a good boy? she asked the terrible Gomer, feeding him a piece of raw steak she’d obtained specifically for this purpose. Who’s a good boy?

In the years since, I have known lots of people whose love has been focused solely on other questionable creatures, some of them evil, such as Gomer, and others just sad and floppy, dogs with all the sentience of a used ShamWow. But oh, the adoration that my friends have had for these wuffly creatures, and with what profound devotion they’ve arranged their days around their needs. One friend of mine has a dog that is kind of like a miniature sloth, with unsettling bits of dried- up Alpo congealed into the fur around its mouth, a crea-ture whose paws for reasons I do not understand can never touch the ground and who must be carried like a clutch purse from spot to spot. She calls him her “little man.” She’s always telling me about how much Bingo loves her, how Bingo’s the only one who understands her, how her life would be empty were it not for the radiant adoration little Bingo sends forth.

I am not in the business of questioning the love that anyone has for anyone else, so let’s agree: whatever she and Bingo have going on is their own sweet business.

But if you ask me, the magic of dogs is not that their love for us is unconditional. What’s unconditional is the love that we have for them.

Listen: If we’re going to talk about dogs, we’re going to have to talk about love, and the sooner you get your mind around this, the more irritated with me you can be. I’ll try to be brief.

I’m pretty sure that if there is any reason why we are here on this planet, it is in order to love one another. It is, as the saying goes, all ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.

And yet, as it turns out, nothing is harder than loving human beings.

In part, this is because we don’t know what we want. Or, on those unlikely occasions when we do know what we want, we often don’t know how to put our desire into words.

Instead, a lot of the time we act like my old friend Gomer, snarling and slathering at the end of our chains, driven to fury not only by our imprisonment but also by the presence of others who appear to us to be undeservedly walking free.

A lot of the time, the one thing we’re here to do is the thing that we’re actually not all that good at. When we try to express the thing we feel, most of the time it comes out wrong. No, wait, I have found myself saying over and over again, perhaps more than any other phrase I have uttered in this life. That’s not what I meant!

On the other hand, given how inarticulate we are in the language of love, we’re absolutely fluent when it comes to expressing our hate.

This is a book about dogs: the love we have for them and the way that love helps us understand the people we have been.

This is a book about men and boys, written by a woman who remembers the world in which they live the way an emigrant might, late in life, recall the distant country of her birth. Back when I lived in the Olde Country— like many men— there were times I found it impossible to express the thing that was in my heart. But the love I felt for dogs was one I never had cause to hide.

This is a book about seven phases of my life and the dogs I loved at each moment.

It’s in the love of dogs, and my love for them, that I can best now take the measure of that vanished boy and his endless desire.

There are times when it is hard for me to fully remember that mysterious child, his ferocity— and his fragility. Sometimes he seems to fade before me, like breath on a mirror.

But I remember the dogs.

__

It’s worth noting what happened on the one day Gomer finally got the thing he’d always wanted, by which I mean my throat.

Gomer’s mistress, Joy, was the manager of a stable. There my sister rode horses and hung out with stable boys who mucked the stalls and listened to the Rolling Stones on a transistor radio. I was just a scarecrow in those days, hanging around the barn with my partner- in- crime, an older boy named Jimmy. That was my name, too, back then anyway, and we were like two mobsters: Jimmy Slingshot (him) and Jimmy Fly- trap (me). We shot wasps’ nests with slingshots; we crept around the perimeter of the nearby Delaware County Prison and watched the convicts planting corn in their orange jumpsuits. We walked across farmers’ fields with his dog, Fleece, who had only one eye. We sat in the leather seats of his brother’s stock car, a coupe that sat up on blocks in the Slingshot family’s garage. Its front fender was crushed, from an accident during the last race the brother had run.

The brother, Bob Junior, wasn’t around anymore. Now he was in Vietnam, flying a chopper. While he was away, Jimmy Slingshot’s father, Bob Senior— who had worked at Boeing developing the very chopper that his son was now flying— turned completely gray.

One day Jimmy Slingshot and I came upon a huge pile of dead pigs in a field. Flies swarmed around them.

What did we do? Just what you’d expect: we got out our slingshots and shot pebbles at the carcasses. That being the custom among our people.

I would, of course, have rather been back at our house, secretly experimenting with my mother’s pink plastic rollers. But how could a person put this desire into words? The only thing you could do with such yearning— even if it was, ultimately, the utter truth of your being— was to keep it locked down in a hole. Or so I then thought.

In the afternoon I left his house and went looking for my sister, who was supposed to be currycombing her pony, Iris, down by the barn. In order to get there, though, I had to walk through Joy’s farm, a place that had clearly once been a thriving enterprise but had fallen on some strange misfortune. The biggest of the old barns had burned down decades before, and it now stood collapsed in upon itself, a tan-gle of stone foundations and charred timbers. A series of old stone steps led from Jimmy Slingshot’s house, down a hill, and into the heart of the old farm’s ruins, a complex that included not only the barn with my sister’s pony but Joy’s home, too, a stone farmhouse surrounded by mud well pocked with hoofprints.

Gomer sat at his usual sentry post, the top step of Joy’s front porch. A chain dangled from his neck.

I tried to slip by him without making eye contact— the dog hated nothing more than eye contact. But I heard the deep growl, and I froze, hoping against hope that motionlessness would make me less contemptible in his sight. In this I was wrong. Gomer leapt to his feet and barked at me with anger and contempt. Again and again he lunged, only to be yanked back by his chain. I felt my heart pounding. I was certain I knew why the dog hated me— it was because he could see into my heart. I know who you are, he snarled. I know who you are!

There were times when I figured everybody knew who I was— that I was not Jimmy Fly- trap at all, that I was, in fact, Jenny Twin- set. I really believed this, right up until the day I finally came out, some thirty years later. It wasn’t that I held, and kept hidden, a nuclear secret that no one ever guessed. No, what I believed was the opposite: that everyone knew I was really a girl but was just too polite to say it.

All too polite, that is, except for creatures such as Gomer, creatures who measured their snarling self- worth in terms of truth telling. I’d recognize the shepherd’s bark in the words of bullies many years later when they said things like I’m sorry to hurt your feelings, but the most important thing is telling you the truth. Which is, if you ask me, often another way of saying The most important thing for me, in fact, is hurting your feelings, and doing so as deeply as I can.

Gomer’s chain snapped, and the dog unexpectedly found himself free.

No one was more surprised at this than Gomer, and the shepherd paused for a moment at the bottom of the wooden stairs, doubting his good fortune. The dog looked back at the house for a moment, as if he expected that the only possible consequence of finally getting free was someone coming along in that very same instant to chain him up again. In this, if only he’d known it, the dog and I turned out to have some common ground.

Instead, he turned toward me and lunged.

I was not fast on my feet, then or now, but I tried to outrun Gomer. I heard his furious snarling just behind me, along with what sounded like the chomp of the dog’s teeth as they snapped through empty space. Finally his front paws struck me in the middle of the back, and I fell into the wet mud that surrounded Joy’s farmhouse.

I lay on my stomach and closed my eyes, thinking the eleven- year- old equivalent of Father, into Thy hands I commend my spirit. The dog had his front paws on my spine. I felt his terrible breath on my neck. He barked triumphantly. I got you, Jenny Twin- set, he suggested. I got you.

And then, incredibly, I felt his tongue on my cheek.

Gomer sniffed me. Then he licked me again. The tongue was wet and rough.

A door slammed. Joy came out of the farmhouse, a ruddy- faced woman with short hair and muddy boots. “What’s going on out here?” she said with irritation, as if somehow, whatever this situa-tion was, it was something I had brought upon myself, and— who knows?— maybe in this suspicion she was not wrong.

I heard her boots sucking through the mud, and then, as I rolled over, I saw her towering above me, reaching down for the links of Gomer’s broken chain.

“Good boy,” she said in a voice that seemed to contain both affection, and pity. “You’re a good boy.” For a moment I thought, Wait, I am? Then the inevitable conclusion ensued: She means the dog.

In the long years since then, I have often wondered what exactly about that boy was good. Surely it was not the terrorization of an eleven- year- old nerd that Joy was singling out for special praise. True, Joy was no fan of mine; she knew full well what Jimmy Slingshot and I were up to when we were out of her sight. Still, it couldn’t have given her any pleasure— or not much, anyhow— to see me on the ground, literally afraid for my life.

No, what Joy must have felt for Gomer at that moment was grat-itude for his protection. She was a woman who lived a hard life on a half- abandoned farm, and as difficult as it was for my young self to imagine, there were likely many moments when she felt vulnerable and scared. That frightening prison with its Victorian tower was less than a mile away, and now and again the word went out: a convict had gone over the wall. There were more than a few times that Jimmy Slingshot and I had been told to stay inside during a prison break, while police combed through the woods with bloodhounds and flashlights.

Sometimes I wondered who it was that had killed all those pigs Jimmy Slingshot and I had found piled up in the field. Had it been an escaped prisoner, who’d done it simply out of malice and revenge?

Maybe, in addition to being a felon, he was a vegetarian.

You don’t think of adults as being scared or vulnerable when you’re a child, but the older you get, the more you understand that the world is a frightening place and that anyone standing between you and the universe’s unseen terrors is someone for whom you can feel tremendous gratitude, even a kind of reverence. It did not matter that the person Gomer was protecting Joy from was a feline nerd who kept seahorses in a tank in his bedroom. What mattered was that even she sometimes felt alone and afraid and that in these moments Gomer made her heart feel less broken.

In his own slathering way, by knocking me to the ground, Gomer had demonstrated to Joy that something stood between her and dan-ger. And by this action, as alone as she might have felt in the world, she knew she was not unloved.

__

One day in 2017, not long after Indigo died, I got a call from the place where we board our dogs when we’re out of town, a “bed’n biscuit” called Willow Run. One of their customers was dying of cancer. Her dog, Chloe, was a black Lab, and she needed a home. We rolled our eyes.

They had to be kidding. We had been in mourning ever since we lost Indigo, and not just because the dog we had loved was gone but because the people we had been seemed to have vanished as well. We were just too banged up. We told them we were sorry, but no.

Then, one weekend when I picked up Ranger after an overnight at Willow Run, I met this Chloe. Her face was soft.

I asked, Maybe I could just take her home for a day? Well, you know how this story goes.

When Chloe entered our house, she was cautious and uncertain. She spent hours that first day going to every corner, sniffing things out. At the end of the day she sat down by the fireplace and gave me a look. If you wanted, she said, I would stay with you.

Soon enough, Ranger had a new wing- dog.

I had hopes of having a conversation with Chloe’s owner before the end, trying to learn what their history had been. I wanted to bring Chloe over to her house so her owner could know that her dog had a good home and so that the two of them could have a proper farewell.

When I finally got through, though, I learned that Chloe’s owner had died the week before.

It snowed that night, and I woke up in a room made mysterious by light and stillness. In the morning I sat up and found that Chloe had climbed into bed with us as we slept.

Well? she asked. I touched her soft ears in the bright, quiet room and thought about the gift of grace.

If you wanted, I said, I would stay with you, too.