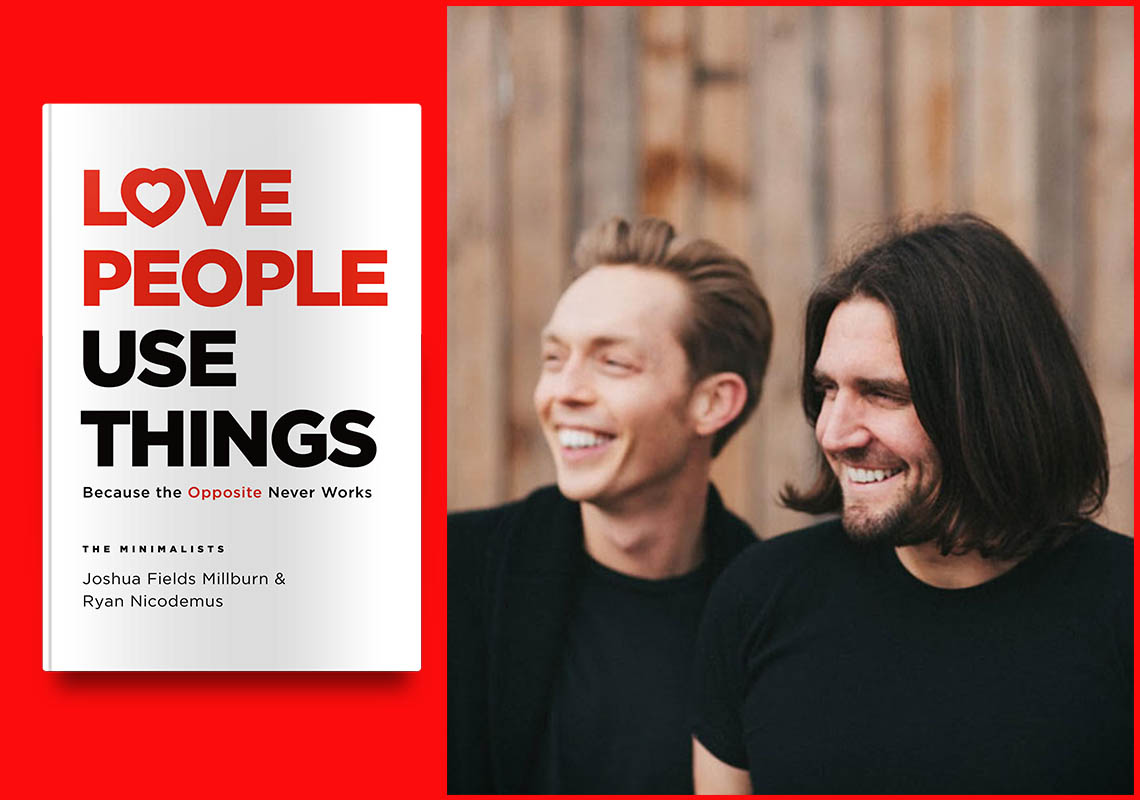

Most people think of minimalism as owning less “stuff.” But Joshua Fields Millburn — one half of The Minimalists — has a different view. In his new book, LOVE PEOPLE, USE THINGS, he — along with partner Ryan Nicodemus — explains how detaching from nonessential possessions actually increases your ability to focus on essential relationships, leading to a more fulfilled life.

Celadon: Many people define minimalism as having less, but you have a unique view of the concept. Please tell us what minimalism means to you, and why it’s so important to lead a fulfilled life.

Joshua Fields Millburn: Minimalism is the thing that gets us past the things so we can make room for life’s most important things — which aren’t things at all. At first glance, it’s easy to think the point of minimalism is only to get rid of material possessions. Decluttering. Simplifying. Eliminating. Jettisoning. Detaching. Paring down. Letting go. If that were the case, then everyone could rent a dumpster and throw all their junk in it and immediately experience perpetual bliss. But, of course, you could toss everything and be miserable. It is possible to come home to an empty house and feel worse because you’ve removed your pacifiers.

Extracting the excess stuff is an essential part of the recipe — but it’s only one ingredient. And if we’re concerned solely with the material goods, then we’re missing the larger point. Getting rid of the clutter is not the end result — it is merely the first step. Sure, you’ll feel a weight lifted, but you won’t experience lasting contentment by pitching all your possessions. That’s because consumption is not the problem — consumerism is. And we can change that by being more deliberate with the decisions we make every day. True, we all need some stuff; the key is to own the appropriate amount of stuff and let go of the rest. That’s where minimalism enters the picture.

Minimalists don’t focus on having less, less, less; they focus on making room for more: more time, more passion, more creativity, more experiences, more contribution, more contentment, more freedom. Clearing the clutter from life’s path creates room for the intangibles that make life rewarding.

Celadon: LOVE PEOPLE, USE THINGS is filled with examples of people that used minimalism to improve their essential relationships. Can you share one story that really stood out to you while writing the book?

JFM: I first met Jason and Jennifer Kirkendoll in the post-show hug line at one of The Minimalists’ live events. They told me that when they married, at age 24, they were both filled with hope for their future. Before they knew it, they were living the American Dream: four kids, two dogs, a cat, and a home in Kansas City.

In time, however, their dream slowly devolved into a nightmare.

The house that was once their dream home no longer fit their ever-expanding lifestyle. So they found a bigger home in a distant suburb, taking on the burden of a larger 30-year mortgage and a longer commute.

The expansion didn’t stop with their home. To keep up appearances, they bought new cars every few years and outfitted their walk-in closets with designer clothes. To alleviate their anxiety, they went shopping on the weekends. They ate too much junk food, watched too much junk TV, and distracted themselves with too much junk on the internet, exchanging a meaningful life for ephemera.

Then, on Christmas morning in 2016, they discovered a fresh perspective. With the carpet under their Christmas tree bare from the morning’s unwrapping, Jennifer turned on Netflix, like she had hundreds of times before, and stumbled across a movie called Minimalism: A Documentary About the Important Things. She found herself contrasting the simple lives on the screen with the heaps of wrapping paper, empty boxes, and untouched gifts strewn across her living-room floor.

Jason and Jennifer knew they needed to make a change. They rented a dumpster and placed it next to their overstuffed house. As January 2017 came to a close, Jason and Jennifer were nearly finished excising their home of its excess. Within a week, the dumpster would be gone, and years of unintentional hoarding would be removed from their lives forever.

Then — the unexpected.

The day before its scheduled retrieval, their dumpster caught fire, and by the time they returned from work, their house had burned to the ground, including everything they wanted to keep.

Fortunately, their kids had been at school during the conflagration, and all three pets had escaped through the doggie door at the back of the house. But everything else was gone.

A month earlier, Jason and Jennifer would have been devastated by this setback. But with their new perspective, they didn’t see it as a setback — it was an inconvenient push forward. Now, with everything out of the way, their only question was: What are we going to do with our newfound freedom?

Celadon: You’ve published three other books about minimalism and your minimalist journey. How is this book different from those titles?

JFM: The title Love People, Use Things was inspired by two unlikely muses. It was the venerable Fulton J. Sheen, circa 1925, who first said, “You must remember to love people and use things, rather than to love things and use people.” I encountered this epigram almost daily as a child, every time I walked past my catholic mother’s bedroom and saw it, cheaply framed and mounted, on the wall above her bed. Nearly a century later, pop-rap superstar Aubrey “Drake” Graham echoed Sheen’s line when he sang, “I wish you would learn to love people and use things and not the other way around.” The Minimalists reworked this sentiment to create the catchphrase that has come to define our message: “Love people and use things because the opposite never works,” which ends every episode of our podcast. When Ryan and I close our live events with this line, the crowd often echoes the phrase in unison. Thousands of people have downloaded the “Love People Use Things” smartphone wallpaper from our website, and a few brave souls have even tattooed it on their bodies as a permanent daily reminder.

Minimalism itself is not a new idea: The concept dates back to the Stoics, to every major religion, and, more recently, to Emerson and Thoreau and Tyler Durden. What’s new is the problem: Never before have people been more seduced by materialism, and never before have people been so willing to forsake loved ones to acquire heaps of meaningless stuff.

With this book, we shine a new light on those time-tested solutions, one lesson at a time. The aim isn’t to remove the reader from the modern world, but rather to show them how to better live within it.

Ryan and I do so by examining the seven essential relationships that make us who we are: stuff, truth, self, values, money, creativity, and people. These relationships crisscross our lives in unexpected ways, providing destructive patterns that frequently repeat themselves, too often left unexamined because we have buried them beneath materialistic clutter. We skate along the surface until the thin ice breaks — we lose our job, we lose a loved one, our house burns down — and then we plunge into the murky depths, unable to save ourselves. Confronted and explored, this book offers the tools to help in the fight against consumerism, clearing the slate to make room for a meaningful life.

Unlike our first three books — a self-help book (Minimalism, 2011), a memoir (Everything That Remains, 2014), and an essay collection (Essential, 2015) — this book will examine the lives of people who have let go of their excess and improved their relationships as a result. After a decade of working with individuals and families, we’ve found a group of common problems and proven solutions that can help you simplify and prioritize your life.

Celadon: How can your brand of minimalism help people struggling in this current climate?

JFM: As I finished writing the final chapter of this book in the spring of 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic was seizing the globe. Today, our “new normal” feels grossly abnormal. With the twin terrors of financial and physical uncertainty, an undercurrent of angst continues to pulse through our days. But perhaps there’s a way to find calm — and even to thrive — in an atmosphere of chaos.

I didn’t know it at the onset of this project, but while quarantined in my home with my wife and daughter during the pandemic, I realized Ryan and I had spent the last two years writing not just a relationships book, but, in many ways, a pandemic-preparation manual. If only we could have gotten this book into the hands of the millions of people who were going to be affected by the pandemic — especially those in debt, those whose priorities aren’t shaped by their values, those consumed by consumption — before the spread of the virus. We would have prevented a great deal of heartache because intentional living is the best form of preparation. You can’t trade canned corn and ammunition for the support and trust of a loving community. You can survive, however, if you need less, and you can thrive, especially in a crisis, if your relationships are thriving.

A pandemic has a sneaky way of putting things in perspective. It took a catastrophe for many people to understand that an economy predicated on exponential growth isn’t a healthy economy — it’s a vulnerable one. If an economy collapses when people buy only their essentials, then it was never as strong as we pretended.

When it comes to simple living, the minimalist movement described in Love People Use Things gained popularity online in the aftermath of the 2008 crash. People were yearning for a solution to their newly discovered problem of debt and overconsumption. Alas, over the past dozen years, we’ve once again grown too comfortable. But the enemy isn’t only consumerism now — it’s decadence and distraction, both material and not.

Amid the panic of the pandemic, I noticed many folks grappling with the question Ryan and I have been attempting to answer for more than a decade: What is essential? Of course, the answer is highly individual. Too often, we conflate essential items with both nonessential items and junk.

In an emergency, not only must we jettison the junk, but many of us are forced to temporarily deprive ourselves of nonessentials — those things that add value to our lives during regular times, but aren’t necessary during an emergency. If we can do this, we can discover what is truly essential, and then we can eventually reintroduce the nonessentials slowly, in a way that enhances and augments our lives, but doesn’t clutter them with junk.

To complicate matters, “essential” changes as we change. What was essential five years ago — or even five days ago — may not be essential now, and so we must continually question, adjust, let go. This is especially true during a crisis, where a week feels like a month; a month, a lifetime.

With the most recent financial depression and a renewed search for meaning, our society will be forced to cope with some critical realities in the not too distant future. Many new norms have been established; others will continue to form as we move forward. Some of us will attempt to cling to the past — to “return to normal” — but that’s like struggling to hold a block of ice in our hands: Once it melts, it’s gone. I’ve been asked: When is this going to turn around? Frankly, I hope it doesn’t. “Turning around” presupposes that we return to the past, to a “normal” that wasn’t working for most people — at least not in any meaningful way. While I don’t know what the future holds, I hope we emerge from this uncertainty with a new normal, one that is predicated on intentionality and community, rather than “consumer confidence.”

To get there, we must simplify again.

We must clear the clutter to find the path forward.

We must find the hope beyond the horizon.

Maybe we needed this. Maybe it’s our wake-up call. Let us not waste this opportunity to question the status quo, to let go, to start anew. The best time to simplify was a decade ago. The second best time is now.